The Ancient Greek playwright Euripides once said: “Every man is like the company he is wont to keep.” We are defined by our relationships. Nowhere is this more true than in category theory. If we want to single out a particular object in a category, we can only do this by describing its pattern of relationships with other objects (and itself). These relationships are defined by morphisms.

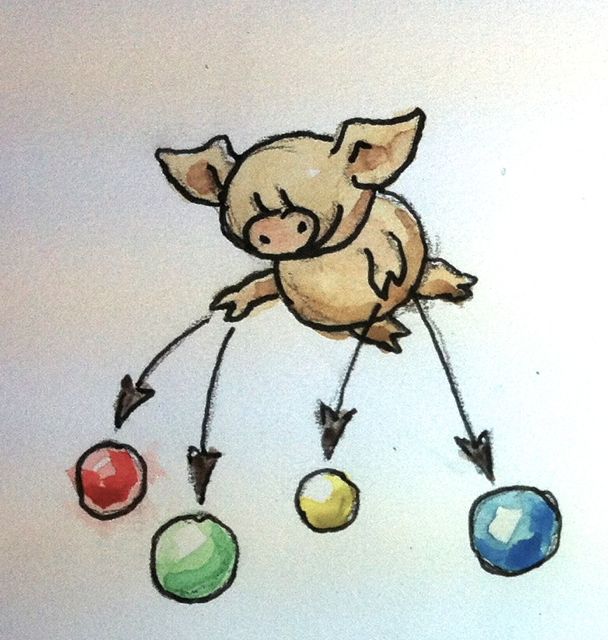

There is a common construction in category theory called the universal construction for defining objects in terms of their relationships. One way of doing this is to pick a pattern, a particular shape constructed from objects and morphisms, and look for all its occurrences in the category. If it's a common enough pattern, and the category is large, chances are you'll have lots and lots of hits. The trick is to establish some kind of ranking among those hits, and pick what could be considered the best fit.

This process is reminiscent of the way we do web searches. A query is like a pattern. A very general query will give you large recall: lots of hits. Some may be relevant, others not. To eliminate irrelevant hits, you refine your query. That increases its precision. Finally, the search engine will rank the hits and, hopefully, the one result that you're interested in will be at the top of the list.

The simplest shape is a single object. Obviously, there are as many instances of this shape as there are objects in a given category. That's a lot to choose from. We need to establish some kind of ranking and try to find the object that tops this hierarchy. The only means at our disposal are morphisms. If you think of morphisms as arrows, then it's possible that there is an overall net flow of arrows from one end of the category to another. This is true in ordered categories, for instance in partial orders. We could generalize that notion of object precedence by saying that object a is “more initial” than object b if there is an arrow (a morphism) going from a to b. We would then define the initial object as one that has arrows going to all other objects. Obviously there is no guarantee that such an object exists, and that's okay. A bigger problem is that there may be too many such objects: The recall is good, but precision is lacking. The solution is to take a hint from ordered categories — they allow at most one arrow between any two objects: there is only one way of being less-than or equal-to another object. Which leads us to this definition of the initial object:

The initial object is the object that has one and only one morphism going to any object in the category.

However, even that doesn't guarantee the uniqueness of the initial object (if one exists). But it guarantees the next best thing: uniqueness up to isomorphism. Isomorphisms are very important in category theory, so I'll talk about them shortly. For now, let's just agree that uniqueness up to isomorphism justifies the use of “the” in the definition of the initial object.

Here are some examples: The initial object in a partially ordered set (often called a poset) is its least element. Some posets don't have an initial object — like the set of all integers, positive and negative, with less-than-or-equal relation for morphisms.

In the category of sets and functions, the initial object is the empty set. Remember, an empty set corresponds to the Haskell type Void (there is no corresponding type in C++) and the unique polymorphic function from Void to any other type is called absurd:

absurd :: Void -> a

It's this family of morphisms that makes Void the initial object in the category of types.

Let's continue with the single-object pattern, but let’s change the way we rank the objects. We'll say that object a is “more terminal” than object b if there is a morphism going from b to a (notice the reversal of direction). We'll be looking for an object that's more terminal than any other object in the category. Again, we will insist on uniqueness:

The terminal object is the object with one and only one morphism coming to it from any object in the category.

And again, the terminal object is unique, up to isomorphism, which I will show shortly. But first let's look at some examples. In a poset, the terminal object, if it exists, is the biggest object. In the category of sets, the terminal object is a singleton. We've already talked about singletons — they correspond to the void type in C++ and the unit type () in Haskell. It's a type that has only one value — implicit in C++ and explicit in Haskell, denoted by (). We've also established that there is one and only one pure function from any type to the unit type:

unit :: a -> () unit _ = ()

so all the conditions for the terminal object are satisfied.

Notice that in this example the uniqueness condition is crucial, because there are other sets (actually, all of them, except for the empty set) that have incoming morphisms from every set. For instance, there is a Boolean-valued function (a predicate) defined for every type:

yes :: a -> Bool yes _ = True

But Bool is not a terminal object. There is at least one more Bool-valued function from every type:

no :: a -> Bool no _ = False

Insisting on uniqueness gives us just the right precision to narrow down the definition of the terminal object to just one type.

You can't help but to notice the symmetry between the way we defined the initial object and the terminal object. The only difference between the two was the direction of morphisms. It turns out that for any category C we can define the opposite category Cop just by reversing all the arrows. The opposite category automatically satisfies all the requirements of a category, as long as we simultaneously redefine composition. If original morphisms f::a->b and g::b->c composed to h::a->c with h=g∘f, then the reversed morphisms fop::b->a and gop::c->b will compose to hop::c->a with hop=fop∘gop. And reversing the identity arrows is a (pun alert!) no-op.

Duality is a very important property of categories because it doubles the productivity of every mathematician working in category theory. For every construction you come up with, there is its opposite; and for every theorem you prove, you get one for free. The constructions in the opposite category are often prefixed with “co”, so you have products and coproducts, monads and comonads, cones and cocones, limits and colimits, and so on. There are no cocomonads though, because reversing the arrows twice gets us back to the original state.

It follows then that a terminal object is the initial object in the opposite category.

As programmers, we are well aware that defining equality is a nontrivial task. What does it mean for two objects to be equal? Do they have to occupy the same location in memory (pointer equality)? Or is it enough that the values of all their components are equal? Are two complex numbers equal if one is expressed as the real and imaginary part, and the other as modulus and angle? You'd think that mathematicians would have figured out the meaning of equality, but they haven't. They have the same problem of multiple competing definitions for equality. There is the propositional equality, intensional equality, extensional equality, and equality as a path in homotopy type theory. And then there are the weaker notions of isomorphism, and even weaker of equivalence.

The intuition is that isomorphic objects look the same — they have the same shape. It means that every part of one object corresponds to some part of another object in a one-to-one mapping. As far as our instruments can tell, the two objects are a perfect copy of each other. Mathematically it means that there is a mapping from object a to object b, and there is a mapping from object b back to object a, and they are the inverse of each other. In category theory we replace mappings with morphisms. An isomorphism is an invertible morphism; or a pair of morphisms, one being the inverse of the other.

We understand the inverse in terms of composition and identity: Morphism g is the inverse of morphism f if their composition is the identity morphism. These are actually two equations because there are two ways of composing two morphisms:

f . g = id g . f = id

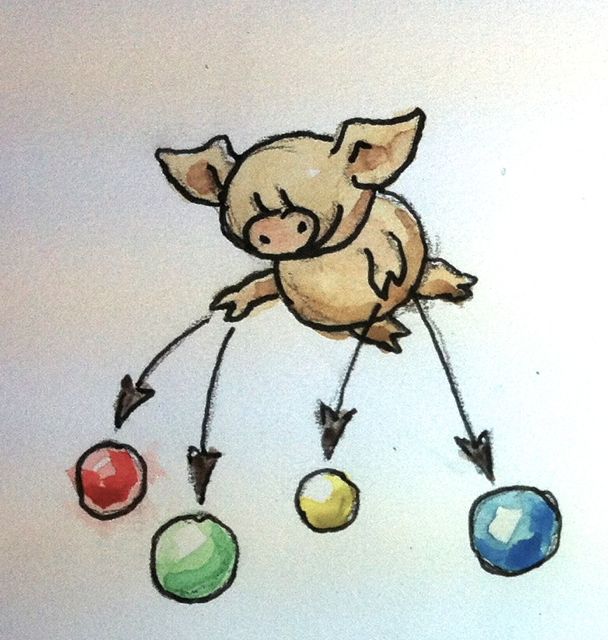

When I said that the initial (terminal) object was unique up to isomorphism, I meant that any two initial (terminal) objects are isomorphic. That’s actually easy to see. Let's suppose that we have two initial objects i1 and i2. Since i1 is initial, there is a unique morphism f from i1 to i2. By the same token, since i2 is initial, there is a unique morphism g from i2 to i1. What's the composition of these two morphisms?

The composition g∘f must be a morphism from i1 to i1. But i1 is initial so there can only be one morphism going from i1 to i1. Since we are in a category, we know that there is an identity morphism from i1 to i1, and since there is room for only one, that must be it. Therefore g∘f is equal to identity. Similarly, f∘g must be equal to identity, because there can be only one morphism from i2 back to i2. This proves that f and g must be the inverse of each other. Therefore any two initial objects are isomorphic.

Notice that in this proof we used the uniqueness of the morphism from the initial object to itself. Without that we couldn't prove the “up to isomorphism” part. But why do we need the uniqueness of f and g? Because not only is the initial object unique up to isomorphism, it is unique up to unique isomorphism. In principle, there could be more than one isomorphism between two objects, but that's not the case here. This “uniqueness up to unique isomorphism” is the important property of all universal constructions.

The next universal construction is that of a product. We know what a cartesian product of two sets is: it’s a set of pairs. But what’s the pattern that connects the product set with its constituent sets? If we can figure that out, we'll be able to generalize it to other categories.

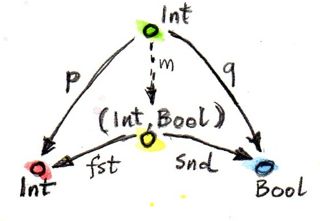

All we can say is that there are two functions, the projections, from the product to each of the constituents. In Haskell, these two functions are called fst and snd and they pick, respectively, the first and the second component of a pair:

fst :: (a, b) -> a fst (x, y) = x

snd :: (a, b) -> b snd (x, y) = y

Here, the functions are defined by pattern matching their arguments: the pattern that matches any pair is (x, y), and it extracts its components into variables x and y.

These definitions can be simplified even further with the use of wildcards:

fst (x, _) = x snd (_, y) = y

In C++, we would use template functions, for instance:

template<class A, class B>

A fst(pair<A, B> const & p) {

return p.first;

}

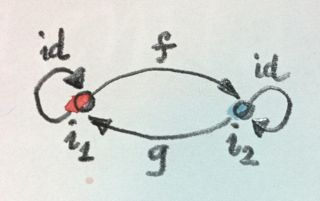

Equipped with this seemingly very limited knowledge, let’s try to define a pattern of objects and morphisms in the category of sets that will lead us to the construction of a product of two sets, a and b. This pattern consists of an object c and two morphisms p and q connecting it to a and b, respectively:

p :: c -> a q :: c -> b

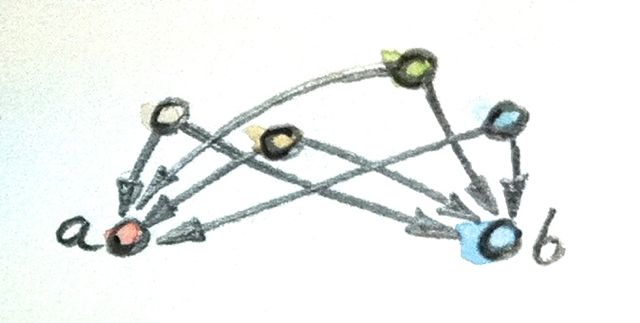

All cs that fit this pattern will be considered candidates for the product. There may be lots of them.

For instance, let’s pick, as our constituents, two Haskell types, Int and Bool, and get a sampling of candidates for their product.

Here’s one: Int. Can Int be considered a candidate for the product of Int and Bool? Yes, it can — and here are its projections:

p :: Int -> Int p x = x q :: Int -> Bool q _ = True

That’s pretty lame, but it matches the criteria.

Here’s another one: (Int, Int, Bool). It’s a tuple of three elements, or a triple. Here are two morphisms that make it a legitimate candidate (we are using pattern matching on triples):

p :: (Int, Int, Bool) -> Int p (x, _, _) = x q :: (Int, Int, Bool) -> Bool q (_, _, b) = b

You may have noticed that while our first candidate was too small — it only covered the Int dimension of the product; the second was too big — it spuriously duplicated the Int dimension.

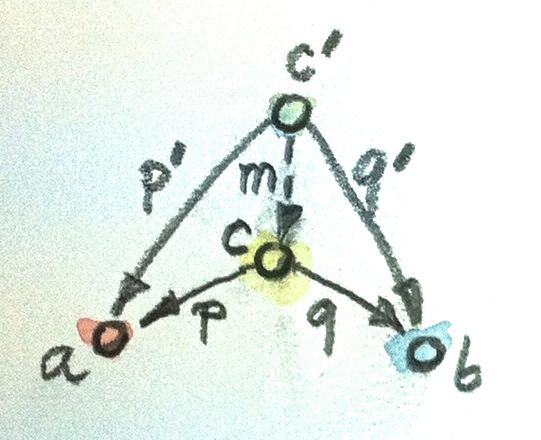

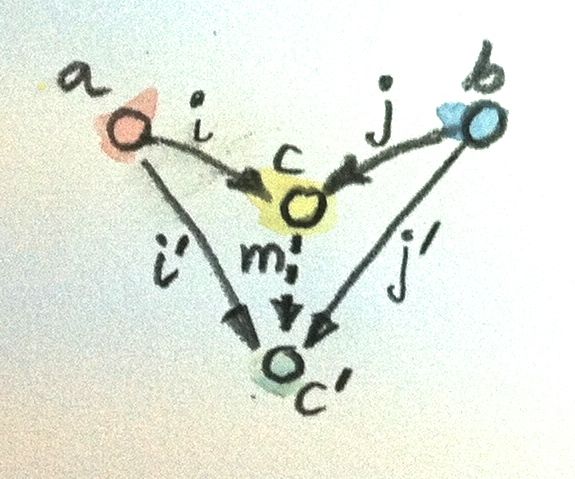

But we haven't explored yet the other part of the universal construction: the ranking. We want to be able to compare two instances of our pattern. We want to compare one candidate object c and its two projections p and q with another candidate object c’ and its two projections p’ and q’. We would like to say that c is “better” than c’ if there is a morphism m from c’ to c — but that’s too weak. We also want its projections to be “better,” or “more universal,” than the projections of c’. What it means is that the projections p’ and q’ can be reconstructed from p and q using m:

p’ = p . m q’ = q . m

Another way of looking at these equation is that m factorizes p’ and q’. Just pretend that these equations are in natural numbers, and the dot is multiplication: m is a common factor shared by p’ and q’.

Just to build some intuitions, let me show you that the pair (Int, Bool) with the two canonical projections, fst and snd is indeed better than the two candidates I presented before.

The mapping m for the first candidate is:

m :: Int -> (Int, Bool) m x = (x, True)

Indeed, the two projections, p and q can be reconstructed as:

p x = fst (m x) = x q x = snd (m x) = True

The m for the second example is similarly uniquely determined:

m (x, _, b) = (x, b)

We were able to show that (Int, Bool) is better than either of the two candidates. Let’s see why the opposite is not true. Could we find some m' that would help us reconstruct fst and snd from p and q?

fst = p . m’ snd = q . m’

In our first example, q always returned True and we know that there are pairs whose second component is False. We can’t reconstruct snd from q.

The second example is different: we retain enough information after running either p or q, but there is more than one way to factorize fst and snd. Because both p and q ignore the second component of the triple, our m’ can put anything in it. We can have:

m’ (x, b) = (x, x, b)

or

m’ (x, b) = (x, 42, b)

and so on.

Putting it all together, given any type c with two projections p and q, there is a unique m from c to the cartesian product (a, b) that factorizes them. In fact, it just combines p and q into a pair.

m :: c -> (a, b) m x = (p x, q x)

That makes the cartesian product (a, b) our best match, which means that this universal construction works in the category of sets. It picks the product of any two sets.

Now let's forget about sets and define a product of two objects in any category using the same universal construction. Such product doesn't always exist, but when it does, it is unique up to a unique isomorphism.

A product of two objects a and b is the object c equipped with two projections such that for any other object c' equipped with two projections there is a unique morphism m from c' to c that factorizes those projections.

A (higher order) function that produces the factorizing function m from two candidates is sometimes called the factorizer. In our case, it would be the function:

factorizer :: (c -> a) -> (c -> b) -> (c -> (a, b)) factorizer p q = \x -> (p x, q x)

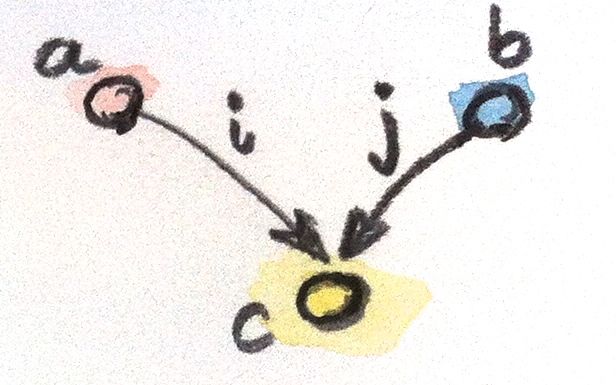

Like every construction in category theory, the product has a dual, which is called the coproduct. When we reverse the arrows in the product pattern, we end up with an object c equipped with two injections, i and j: morphisms from a and b to c.

i :: a -> c j :: b -> c

The ranking is also inverted: object c is “better” than object c' that is equipped with the injections i' and j' if there is a morphism m from c to c' that factorizes the injections:

i' = m . i j' = m . j

The “best” such object, one with a unique morphism connecting it to any other pattern, is called a coproduct and, if it exists, is unique up to unique isomorphism.

A coproduct of two objects a and b is the object c equipped with two injections such that for any other object c' equipped with two injections there is a unique morphism m from c to c' that factorizes those injections.

In the category of sets, the coproduct is the disjoint union of two sets. An element of the disjoint union of a and b is either an element of a or an element of b. If the two sets overlap, the disjoint union contains two copies of the common part. You can think of an element of a disjoint union as being tagged with an identifier that specifies its origin.

For a programmer, it's easier to understand a coproduct in terms of types: it's a tagged union of two types. C++ supports unions, but they are not tagged. It means that in your program you have to somehow keep track which member of the union is valid. To create a tagged union, you have to define a tag — an enumeration — and combine it with the union. For instance, a tagged union of an int and a char const * could be implemented as:

struct Contact {

enum { isPhone, isEmail } tag;

union { int phoneNum; char const * emailAddr; };

};

The two injections can either be implemented as constructors or as functions. For instance, here's the first injection as a function PhoneNum:

Contact PhoneNum(int n) {

Contact c;

c.tag = isPhone;

c.phoneNum = n;

return c;

}

It injects an integer into Contact.

A tagged union is also called a variant, and there is a very general implementation of a variant in the boost library, boost::variant.

In Haskell, you can combine any data types into a tagged union by separating data constructors with a vertical bar. The Contact example translates into the declaration:

data Contact = PhoneNum Int | EmailAddr String

Here, PhoneNum and EmailAddr serve both as constructors (injections), and as tags for pattern matching (more about this later). For instance, this is how you would construct a contact using a phone number:

helpdesk :: Contact; helpdesk = PhoneNum 2222222

Unlike the canonical implementation of the product that is built into Haskell as the primitive pair, the canonical implementation of the coproduct is a data type called Either, which is defined in the standard Prelude as:

Either a b = Left a | Right b

It is parameterized by two types, a and b and has two constructors: Left that takes a value of type a, and Right that takes a value of type b.

Just as we've defined the factorizer for a product, we can define one for the coproduct. Given a candidate type c and two candidate injections i and j, the factorizer for Either produces the factoring function:

factorizer :: (a -> c) -> (b -> c) -> Either a b -> c factorizer i j (Left a) = i a factorizer i j (Right b) = j b

We've seen two set of dual definitions: The definition of a terminal object can be obtained from the definition of the initial object by reversing the direction of arrows; in a similar way, the definition of the coproduct can be obtained from that of the product. Yet in the category of sets the initial object is very different from the final object, and coproduct is very different from product. We'll see later that product behaves like multiplication, with the terminal object playing the role of one; whereas coproduct behaves more like the sum, with the initial object playing the role of zero. In particular, for finite sets, the size of the product is the product of the sizes of individual sets, and the size of the coproduct is the sum of the sizes.

This shows that the category of sets is not symmetric with respect to the inversion of arrows.

Notice that while the empty set has a unique morphism to any set (the absurd function), it has no morphisms coming back. The singleton set has a unique morphism coming to it from any set, but it also has outgoing morphisms to every set (except for the empty one). As we've seen before, these outgoing morphisms from the terminal object play a very important role of picking elements of other sets (the empty set has no elements, so there's nothing to pick).

It's the relationship of the singleton set to the product that sets it apart from the coproduct. Consider using the singleton set, represented by the unit type (), as yet another — vastly inferior — candidate for the product pattern. Equip it with two projections p and q: functions from the singleton to each of the constituent sets. Each selects a concrete element from either set. Because the product is universal, there is also a (unique) morphism m from our candidate, the singleton, to the product. This morphism selects an element from the product set — it selects a concrete pair. It also factorizes the two projections:

p = fst . m q = snd . m

When acting on the singleton value (), the only element of the singleton set, these two equations become:

p () = fst (m ()) q () = snd (m ())

Since m () is the element of the product picked by m, these equations tell use that the element picked by p from the first set, p (), is the first component of the pair picked by m. Similarly, q () is equal to the second component. This is in total agreement with our understanding that elements of the product are pairs of elements from the constituent sets.

There is no such simple interpretation of the coproduct. We could try the singleton set as a candidate for a coproduct, in an attempt to extract the elements from it, but there we would have two injections going into it rather than two projections coming out of it. They'd tell us nothing about their sources (in fact, we've seen that they ignore the input parameter). Neither would the unique morphism from the coproduct to our singleton. The category of sets just looks very different when seen from the direction of the initial object than it does when seen from the terminal end.

This is not an intrinsic property of sets, it's a property of functions, which we use as morphisms in Set. Functions are, in general, asymmetric. Let me explain.

A function must be defined for every element of its domain set (in programming, we call it a total function), but it doesn't have to cover the whole codomain. We've seen some extreme cases of it: functions from a singleton set — functions that select just a single element in the codomain. (Actually, functions from an empty set are the real extremes.) When the size of the domain is much smaller than the size of the codomain, we often think of such functions as embedding the domain in the codomain. For instance, we can think of a function from a singleton set as embedding its single element in the codomain. I call them embedding functions, but mathematicians prefer to give a name to the opposite: functions that tightly fill their codomains are called surjective or onto.

The other source of asymmetry is that functions are allowed to map many elements of the domain set into one element of the codomain. They can collapse them. The extreme case are functions that map whole sets into a singleton. You've seen the polymorphic unit function that does just that. The collapsing can only be compounded by composition. A composition of two collapsing functions is even more collapsing than the individual functions. Mathematicians have a name for non-collapsing functions: they call them injective or one-to-one

Of course there are some functions that are neither embedding nor collapsing. They are called bijections and they are truly symmetric, because they are invertible. In the category of sets, an isomorphism is the same as a bijection.

Either as a generic type in your favorite language (other than Haskell).Either is a “better” coproduct than int equipped with two injections:int i(int n) { return n; }

int j(bool b) { return b? 0: 1; }

Hint: Define a function

int m(Either const & e);

that factorizes i and j.

int with the two injections i and j cannot be “better” than Either?int i(int n) {

if (n < 0) return n;

return n + 2;

}

int j(bool b) { return b? 0: 1; }

int and bool that cannot be better than Either because it allows multiple acceptable morphisms from it to Either.I'm grateful to Gershom Bazerman for reviewing this post before publication and for stimulating discussions.